Hatshepsut, one of ancient Egypt’s most famous pharaohs, left a lasting legacy in the form of remarkable statues that have been preserved through the ages. Here are five historical statues that pay homage to this extraordinary ruler:

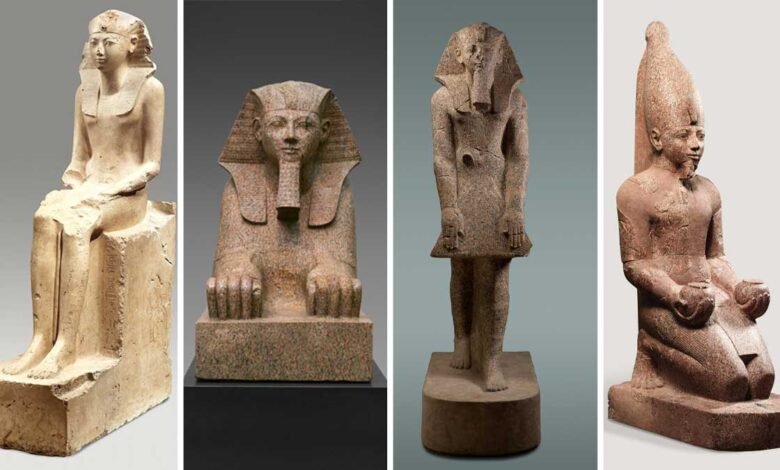

Sphinx of Hatshepsut statue:

The majestic Sphinx of Hatshepsut exemplifies this legendary female pharaoh’s innovative approach to royal representation. Carved from granite, this colossal sculpture depicts Hatshepsut with a lion’s muscular body and a human head wearing the nemes headdress and false beard of a male Egyptian ruler. The sphinx’s sheer physical power contrasts with the serene confidence of Hatshepsut’s idealized facial features. This was one of at least six sphinxes commissioned by Hatshepsut to guard the entrances to her sprawling mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri.

The sphinx held deep symbolic meaning in ancient Egyptian art, with the most famous example being the Great Sphinx of Giza from the 4th dynasty. But Hatshepsut embraced this iconography in a bold new way. She ruled Egypt initially as regent for her nephew and stepson Thutmose III before assuming the full powers of pharaoh herself. Many of her statues present her as the ideal male king – young, vital and authoritative. But the Sphinx of Hatshepsut deftly blended masculine royal power with her own female identity. Its commanding presence announced her unconventional and visionary reign.

While sphinxes representing prior male kings abound in Egyptian art, this sphinx stands apart for depicting a female ruler. Hatshepsut forged innovative combinations of visual imagery to legitimize her authority. The Sphinx of Hatshepsut remains a testament to how she expanded conceptions of kingship to usher in a prosperous new era for Egypt. Her legacy as a brilliant tactician and trailblazing woman leader endures.

Seated Statue of Hatshepsut:

This life-size seated statue offers rare insight into Hatshepsut’s nuanced self-presentation as female pharaoh. Carved from indurated limestone and granite, it shows her seated on a throne wearing the ceremonial nemes headdress and shendyt kilt of an Egyptian king. Despite the traditional masculine garb of a ruler, the statue radiates a remarkably graceful, feminine presence.

Hatshepsut adopted the full titulary and regalia of a pharaoh after ruling Egypt initially as regent for her nephew and stepson, Thutmose III. Many depictions from her reign present her as the idealized king – young, powerful and authoritative. Yet this statue departs from that visual tradition with its elegant proportions and dignified seated pose. Traces of pigment reveal how colors originally enhanced the sophisticated craftsmanship.

The statue’s inscriptions also acknowledge Hatshepsut’s female identity, using feminine grammar and epithets like “Perfect Goddess” and “Bodily Daughter of Re.” This suggests it was intended for offering rituals in the private chapels of her mortuary temple, away from the public’s eye. The Granite Seated Statue of Hatshepsut provides rare insight into how she skillfully balanced royal imagery that affirmed her sovereignty while subtly nodding to the remarkable fact that she ruled Egypt as a woman.

Hatshepsut in a Devotional Attitude

This commanding statue captures the female pharaoh Hatshepsut adopting a reverent, kneeling pose as she offers ritual vessels to the god Amun. Carved from granite, it originally stood alongside a matching statue flanking an entrance to the upper terrace of her Deir el-Bahri mortuary temple. Hatshepsut kneels solemnly, wearing the nemes headdress, false beard and shendyt kilt of an Egyptian king. Her hands clutch two round pots, frozen mid-offering.

In ancient Egypt, the idealized image of the king was a young, vigorous man – regardless of the ruler’s actual age or gender. This statue presents Hatshepsut as the quintessential male monarch, modeling her bold self-presentation as pharaoh. Yet the inscriptions use feminine grammar and titles, subtly acknowledging her female identity.

The statue’s devotional posture and placement in her temple reinforced Hatshepsut’s legitimacy and divine role. Its design quotes earlier Middle Kingdom models, linking her to righteous rulers of the past. This masterful granite sculpture brilliantly blended traditional and innovative details to proclaim Hatshepsut’s right to rule. It remains a crowning exemplar of how she used iconography and architecture to legitimize her authority as a female pharaoh.

Large Kneeling Statue of Hatshepsut

This commanding over-life-size statue depicts Hatshepsut kneeling solemnly with ritual offering vessels clutched in each hand. It originally stood as one of at least ten huge kneeling statues flanking the processional route in her sprawling mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri. Hatshepsut kneels reverently, wearing the uniform of a male Egyptian ruler – a false beard, white crown, and royal kilt. The inscriptions identify her offerings to the god Amun, affirming her spiritual role.

Each kneeling figure was strategically placed along the path traversed by Amun’s image during annual religious festivals. Their sheer size and perfect symmetry powerfully conveyed Hatshepsut’s authority and legitimacy as pharaoh. This particular statue, representing her in the white crown of Upper Egypt, stood on the southern end of the route.

The statue was fragmented and partially destroyed over time. Its head was taken to Berlin in the 19th century before being reunited with the body by the Metropolitan Museum’s excavations in the 1930s. The generous Egyptian Antiquities Service allowed this and other damaged pieces to be restored and displayed. The Large Kneeling Statue of Hatshepsut endures as a testament to the grandeur of her architectural vision and her consummate skill in using art to communicate power.

Sphinx of Hatshepsut statue

This Sphinx of Hatshepsut exemplifies the creative adaptations of traditional Egyptian art made during her reign. The small limestone statue is a reconstructed composite, with missing sections cast from an almost identical sphinx now in Cairo. The two likely flanked the entrance to the upper terrace of Hatshepsut’s Deir el-Bahri mortuary temple.

Unlike Hatshepsut’s colossal sphinxes elsewhere at her temple, this sphinx forgoes the royal nemes headdress in favor of a stylized lion’s mane encircling her human face. It follows a Middle Kingdom sphinx type associated with Pharaoh Amenemhat III centuries prior. Traces of yellow pigment mark the face, the color reserved for women in Egyptian art.

The Sphinx of Hatshepsut deftly merges established imagery with innovative adaptations suiting Hatshepsut’s historic female rule. While asserting her legitimacy as pharaoh, it also nods subtly to her feminine identity through its coloring and softer facial features. Along with the larger sphinxes, this sphinx protected access to Hatshepsut’s sacred temple precinct. Despite its small size, it remains a testament to Hatshepsut’s savvy blending of tradition and invention in art that affirmed her authority.

reference from : https://www.metmuseum.org/search-results?q=Hatshepsut

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!